Akom, which means “possession,” is the Fante religious institution that serves to mediate between the obosom, or nature gods, and the community as a whole. Obosom are believed to have been created by the supreme god Nyame, who, although not worshipped directly, is thought to have created the world and mankind and is felt to be omnipresent and omnipotent. Fante animists recognize numerous obosom that are believed to watch over the activities of humans and to punish those who act contrary to customs of society. The obosom are conceived of as living in objects in the environment –such as trees, stones, wells, or streams–and these objects in turn serve as their shrines. Although the obosom are viewed as having broad ranging powers, any one of these spirits has his or her own area of competence and jurisdiction, e.g., fertility, warfare, agriculture, or general protection to the community.

A priesthood exists in Fante communities to serve as the intermediaries between humans and the obosom. This priesthood consists of individuals, both male and female (although in Anomabo women are in the majority), who have been possessed by a deity and thus called into its service–they are called akomfo, “the possessed ones.” Their calling is followed by a three- to five-year apprenticeship with a senior priestess during which they learn about the character of their deity, about herbal medicines, and how to dance for akom ceremonies.

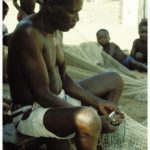

The akomfo do not live together or have a central sanctuary. They enact their public ceremonies throughout the town at or near obosom shrines on propitious days. During a visit one day to the house of a senior akomfo in Anomabu, I was shown fetishes of some of the local obosom.

In order to facilitate communication between the mundane and spirit realms at these ceremonies, the akomfo basically dance themselves into a state of possession. When this state is achieved, they are led away to be interrogated by a specialist knowledgeable in the language of the gods. It is through this process that the thoughts and concerns of the local deities, which might be thought of as basically synonymous with the traditional Fante value system, are made known to the community at large. The ceremonies of the akomfo are public and constitute a form of religious spectacle that is as dramatically compelling to the common Fante as it is spiritually efficacious.

These ceremonies are animated by a distinctive and vibrant form of Fante music that accompanies intricate dancing executed only by the trained priestesses. This is contrary to most other situations in which music is heard in Anomabu, where the norm is that anyone moved to dance is free to do so.

The akom ensemble includes a male chorus singing fragments of songs that the deity requests through the akomfo he or she is possessing. These songs are set to rhythmically dense and intense drumming that works within a time framework marked off by a pair of large handheld bells.

Since there is no other form of Fante music structured or sounding like the music for akom, as soon as a ceremony begins this loud and bold style of drumming immediately attracts a large and curious crowd of spectators. In addition to functioning as a sonic advertisement for the cult event, the music simultaneously facilitates or triggers the attainment of a possession state by trained specialists.

Although specific rhythms and their corresponding dance movements are unique to the akom tradition, the way in which they and the songs performed by the male chorus are combined during a ceremony is quite spontaneous and unpredictable. For the Fante animist, the end result of this organic interaction between musicians and akomfo is communication with the nature deities who are believed to shape, sometimes rather capriciously, the general welfare of the community.

There are numerous akomfo in Anomabu, and hardly a week went by without me running into them performing their ceremony to a large and engaged crowd of onlookers. I would also see them at the large, yearly community celebration of thanksgiving (the Okyir Festival) and on other occasions of significance involving processions through the town. They would not be performing their dance in these contexts, but would be positioned at or near the head of these colorful and mobile displays of the prominent individuals and organizations of the community.