Author: Gina Donovan

Conga

Frankakitsanyi Video

The Research Project

Between 8 October 1992 and 8 June 1993, a span of eight months, I made over seventy visits to the fishing community of Anomabu on the south coast of Ghana, West Africa (I was living and teaching at a university in Cape Coast, a city about fifteen miles to the west of Anomabu). Having taught college courses on African music prior to my arrival in Ghana, my residency afforded me an opportunity to actually experience Africans making music in a narrowly-defined geographic and cultural space. I set about doing this by developing relationships with residents of one community and by attending as many events in that community into which music making was integrated as was possible during the bounded period of my stay in Ghana. Although I cannot claim exhaustive coverage of the musical organizations active in Anomabu at the time of my research, nor can I address the ways in which individuals in this community integrate music into their home life and while at work, I feel safe in characterizing the breadth of groups included here as constituting a strong representative sampling of the community’s communal music-making resources.

I take on the difficult and contestable challenge in this website of constructing a representation of Fante musicking from the shards of documentation that I made and from other researchers’ (all, like myself, cultural outsiders) writings about facets of Fante culture (see Bibliography). As a result, one should understand that the picture of musical life painted here should not be received as THE authoritative representation of musicking in Anomabu (much less in Ghana or in Africa in general), but rather as AN attempt by a cultural outsider to present his sense of the meaning of the music making he observed in this one Fante community.

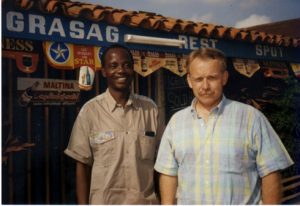

A key figure in facilitating my research in Anomabu was Mr. Kwesi Nana Austin Sagoe, a prominent citizen of the town who was my translator and also helped negotiate permission for me to document on film and tape the material viewable on this site. Transcriptions and translations of song texts are by Mr. Samuel Amissah, a student of mine at the University of Cape Coast. While I made most of the audio and visual documentations heard and seen on this site, some of the video footage and still photography was made by Val Vetter. Our presence in Ghana during 1992-93 was made possible through a Fulbright Visiting Lecturer and Researcher grant.

Okyir (New Year) Festival Video Selections

Video Selections:

Day 3

In the late afternoon of the third day of the Okyir Festival a competition had been organized between traditional music groups from the town. Three groups participated in 1992–odenkese, adzewa and adenkum. A canopy was set up at the edge of the durbar grounds under which the judges and a few invited guests were seated. One at a time, the groups approached the judges and presented two or three numbers. The video clip includes a few seconds of footage of each of the three groups as they approach the judges. That night there was also a vigil held by the town’s akomfo that I did not witness.

Day 4

The fourth day of the festival was its ceremonial climax and included a colorful procession through the town by the community’s key organizations and a festive durbar. The clip begins with the head of the procession, which includes representatives of the akomfo and the paramount chief (including the royal fontomfrom ensemble).

<cross dissolve>

Asafo companies follow–here we see Co. No. 6’s frankakitsanyi waving a company flag followed by the company’s official voice, its asafokyen, upon which texts are being drummed.

<fade out>

The procession makes a stop at the paramount chief’s palace to present libations to ancestors and important local spirits.

<cross dissolve>

The procession is re-organized–here we see the asafo companies being addressed and ordered numerically. A bugle call signals the paramount chief’s emergence from his palace.

<fade out>

The now much filled-out procession recommences on its route to the durbar grounds with the fetish priestesses leading the way and followed by the first two asafo companies.

<cross dissolve>

Later, Asafo Co. No. 6 passes by.

<cross dissolve>

Towards the end of the procession are the chiefs from the Anomabu Traditional Area, with the omanhene (paramount chief) and his entourage (which includes the royal fontomfrom drums) situated at the very end.

<fade out>

Meanwhile, at the durbar grounds the crowd that is already gathering in anticipation of the arrival of the procession is being entertained by a brass band. The grounds, a large open field, are fringed with canopies underneath which spaces have been reserved for the groups participating in the procession.

<fade out>

The procession arrives at the durbar grounds and its participants head for their assigned places.

<cross dissolve>

At the end of the procession is the entourage of the paramount chief.

<fade out>

All sorts of performances take place in a seemingly spontaneous manner on the open grounds. First we see a display of soccer ball handling,

<cross dissolve>

an asafo flag presentation,

<cross dissolve>

the brass band strutting its stuff,

<cross dissolve>

a ribald (and perhaps inebriated) improv group,

<cross dissolve>

the town adenkum group, and

<cross dissolve>

some very flexible acrobats.

<fade out>

Later, the mood becomes more formal as all the official participants shake hands with the omanhene (a symbolic reaffirmation of their allegiance), libations are poured, prayers are spoken and

<cross dissolve>

formal speeches are delivered.

Day 5

Activities on the fifth day of the Okyir Festival take place on the beach next to Fort William. At one time or another in the course of the day, almost everyone will submerge themselves in the ocean for a moment as a symbolic act of cleansing called “sea bathing.”

<cross dissolve>

Other more organized activities include wrestling matches,

<cross dissolve>

displays of group solidarity (e.g., a women’s club singing and dancing),

<cross dissolve>

tug-of-war competitions, and boat races (not shown).

<cross dissolve>

Throughout the day new groups continue to arrive at the beach, often times singing and dancing. In some of the concluding segments the Anomabu apatampa group, dressed in their diagonally-striped outfits, can be seen and heard getting into the spirit of the celebration.

Okyir (New Year) Festival

Most Akan communities, including the Fante town of Anomabu, will mount a festival of thanksgiving once a year to celebrate a successful harvest, to honor ancestors and the spirits of nature, and to reaffirm the social ties that bind the community together. In 1992, Anomabu mounted what it calls its Okyir Festival between October 6 and 11. The video clips included here were made during the final three–and most dramatic–days of the celebration. During the first two days (not documented here), many of the events had to do with cleaning up the town and with spiritual observances (for example, the ceremomial feeding of mashed yams to the obosom). Since I was unable to attend these events, I am not sure how music making was integrated into them. I do know that during the final three days of the festival documented here that there was a great deal of music making enlivening the events.

Enstoolment of Chief Video Selection

Video Selection:

The video clip begins in front of the house of Mr. Ocansey’s mother, where on the second floor he, several local chiefs, and a representative of his asafo organization are meeting. In front of the house we see the palanquin being readied, the granddaughter of Mr. Ocansey dressed in a kente cloth (a chief being carried in a palanquin will always be accompanied by a young relative so that if something tragic should happen to him his spirit will be passed on to his kin), a linguist, and, as the camera pans left, a few akomfo who will lead the impending outdooring procession through town.

<fade out>

The paramount chief’s fontomfrom ensemble, set up across the street, warms up the crowd that is gathered in anticipation of the appearance of Mr. Ocansey and his accompanying officials.

<fade out>

As the officials descend the stairway, Mr. Ocansey is the third in line wearing the lighter-colored kente cloth and holding a ceremonial machete in his right hand. As women hold sheets around the palanquin to shield the spectators’ view of the chief entering it, we can see drummers of an maintain ensemble, which consists primarily of dondo (hourglass) and mpintintao (single-head vessel) drums. I was unsuccessful in finding out where this drumming group came from, but perhaps the drums belong to one of the lesser chiefs in the Anomabu Traditional Area.

<fade out>

Libations are poured to the ancestors whose protection and support is requested for the event.

<fade out>

The palanquin is hoisted onto the heads of the four bearers and the procession is off to the festive cacophony of aben, rounds fired from guns, and the chiefly fontomfrom ensemble.

<fade out>

The procession, with an asafo company immediately in front of the palanquin carrying Mr. Ocansey, makes its way through the town of Anomabu.

<fade out>

The route of the possession includes visits to all seven asafo company posts, at each of which the palanquin circles the shrine while music and gunshots add to the festive mood. Symbolically, these visits to the posts communicate each company’s affirmation of the new chief’s legitimacy and their support of him as a community leader. Here we see the procession circling around the shrine of Asafo Co. No. 1.

<fade out>

We see the entourage exiting from another asafo post. At the head of the procession are representatives of the paramount chief, followed by akomfo, drummers and flag bearers of several asafo companies, the palanquin, and celebrants mostly from Mr. Ocansey’s abusua.

<fade out>

The chief’s fontomfrom ensemble rejoins the procession. A sense of the intensity of this type of drumming can be garnered from this excerpt.

<fade out>

The procession continues through town, with the new chief and his young relative continuously moving to the music and acknowledging the well-wishers.

<fade out>

Once the procession arrives at the palace the palanquin is moved randomly around the courtyard as the mpintin and fontomfrom ensembles continue to provide excitement with their music.

<fade out>

The fontomfrom group strikes up a new piece, inspiring participants to dance. We see some of the invited guests seated under canopies at the edge of the palace courtyard.

<fade out>

The ceremony that followed consisted mostly of speeches, the pouring of libations, and the saying of prayers and oaths of allegiance. There was, however, one brief segment when members of an asafo company provided an unaccompanied song.

Enstoolment of Chief

On Saturday, February 27, 1993, Charles Ocansey was installed as Nana Kobena Kannie I, Nkosohene (a low-level chief) of the Anomabu Traditional Area. A much-respected member of the Anomabu community, the honor of being named a chief was likely bestowed upon Mr. Ocansey in order to include a person of his educational background (he holds business degrees) on the town’s council. As is the case with most ceremonies of this importance, it draws together most of the main constituencies in the community as a display of mutual support. Music making, as usual, plays a prominent role in this community celebration.

Fante and Akan chiefs possess elaborately carved stools that are incorporated into ceremonies as icons of their authority. In death, these stools become ceremonial objects through which they are honored. Because of the symbolic importance of these stools, the Akan refer to the installation of a new chief as his enstoolment.

Funeral for Paramount Chief Video Selections

Video Selections:

Day 1

Around midnight of the previous night, the electricity for the entire town of Anomabu was briefly turned off to insure complete darkness as the Paramount Chief’s body was returned to town (it had been preserved at a morgue in Accra for the previous few months while arrangements for the funeral were being made) and placed on an ornately decorated bed in a second floor room of the palace. This video clip opens with a panoramic shot of the palace where, on this first day of the four-day-long series of events for the funeral, the Anomabu Traditional Area chiefs under the suzerainty of the paramount chief have gathered to ceremoniously inform the ancestors and local spirits of the chief’s death and to request their support in the days to come. Although enacted out in the open, this is not a public affair. The residents of Anomabu have not officially been informed of the death of their chief, although they of course all know of it since he died months earlier.

<fade out>

We see first the court linguist presenting libations at the base of a tree to the chief’s ancestors by pouring gin on the ceremonial stools that had been used by his precursors. The group then moves to a shrine at the front of the palace where further libations are presented to local obosom. Utterances by the linguist are affirmed by those present and the court aben player blasts an occasional text in support of the actions.

<fade out>

A cow is sacrificed to the ancestors, who are symbolically fed by the blood that hits the ground. Later, the cow is butchered for its meat (not shown).

<fade out>

Still later in the morning, Reginald Mensah drums appropriate texts on the royal atumpan, which face the entrance of the palace wherein the chief’s body lays in state.

<fade out>

Local chiefs rest in the palace courtyard between the low-key events of the first day. (The recorded music heard during segments of this video clip is coming from the outdoor speakers of a nearby bar–it has nothing to do with the funeral activities.)

Day 2

The second day of the funeral ceremony is the day on which the local chiefs proclaim to the citizens of Anomabu that their paramount chief has died by making a solemn procession through the streets wearing red and black, the colors Fante associate with death. From this point on, the stages of the ceremony involve ever increasing segments of the community.

Day two begins with the royal fontomfrom ensemble being played at the palace as the chiefs of the Anomabu Traditional Area arrive. The fontomfrom drums and the musicians are set up facing the front wall of the palace, right below the second floor window of the room in which the body of the chief rests. Much progress has been made by this time in preparing the palace courtyard for the events of the third and fourth days.

<cross dissolve>

The local chiefs arrive at the palace after having a planning meeting in a house across the street.

<cross dissolve>

After passing in front of the still playing fontomfrom ensemble, the chiefs circle the palace courtyard before taking their seats.

<fade out>

The drummer from one of the town’s asafo companies calls the chiefs to order to begin the procession.

<fade out>

Having reformed their line, the chief’s begin their procession through the town to the occasional bursts of text on the asafokyen and the aben.

<cross dissolve>

The procession continues through the streets of Anomabu.

<fade out>

After returning to the palace, the chiefs enter the building in order to view the corpse for the first time and pay their respects.

<fade out>

It is considered dangerous for a living chief to see a dead one, so a special ceremony is performed just before the chiefs leave the palace. By walking through the blood of a sacrificed animal, the chiefs will be protected against suffering the same misfortune that has befallen their paramount chief. Before the sheep is sacrificed, libations are poured to the ancestors petitioning their protection. The fontomfrom ensemble begins to play again as the chiefs exit the palace.

Day 3

The third day is when the major community organizations–the asafo companies and the akom priestesses–are drawn into the ceremony. The asafo companies each gather at their respective posts and march through the streets toward the palace with their asafokyen leading the way and their members singing.

The clip begins with Asafo Co. No. 6 in the streets. Then Co. No. 3 passes by them.

<cross dissolve>

Several akomfo in their white cloths approach the palace from another direction, with yet another asafo company following them. This company, No. 5, uses a mirliton (kazoo) instead of an asafokyen.

<fade out>

Meanwhile, at the palace grounds, the royal fontomfrom ensemble is playing in anticipation of the arrival of the participating organizations. Notice that the drums are now facing the courtyard instead of the building, and that, unlike the previous two days, there are many observers present. While the asafo companies are organizing themselves beneath a canopy, the akomfo arrive.

<fade out>

One by one, each asafo company salutes the assembled chiefs and invited guests seated around the periphery of the courtyard with their asafokyen and the presentation of one of their flags. Here we see the asafokyen player and the frankakitsanyi of Co. No. 6 introducing their company to the chiefs.

<fade out>

Throughout the afternoon the various asafo organizations contribute music to enliven the event. As they play and sing (Co. No. 6 is shown here), mourners can be seen walking by on their way to pay their last respects to the deceased chief while others are moved to express themselves through dance.

<cross dissolve>

A company frankakitsanyi joins the dancers. The group of women in red and black that dances their way through the courtyard are members of the chief’s abusua (matriclan). What you are seeing and hearing in the footage is not, so far as I can tell, thought of as entertainment by the Fante. Rather, it is viewed as a desirable state of sound that invites participants to explore their feelings of loss through dance.

Day 4

In the palace courtyard, we see the key representatives of the local chiefs and the paramount chief’s abusua leaving the palace to the accompaniment of the atumpan drums and aben.

<cross dissolve>

With the fontomfrom ensemble now being played, we see the local chiefs and their regalia (e.g., linguist staffs with sculptural representations of proverbs) seated underneath a tent.

<cross dissolve>

A royal aben player.

<fade out>

Meanwhile, the entourages of paramount chiefs from around the Central Region are organizing on the edge of town in preparation for their grand procession to the palace grounds. The regalia of chieftancy include ivory aben (sometimes with a bell-like extension made from the jawbones of enemies killed in long-ago battles), sculptured finials on linguists’ staffs, small executioner drums (executions are no longer carried out, but most courts will still have a person in this ceremonial role), large and colorful umbrellas, thrones, and a royal music ensemble.

Our first view of the procession shows a royal aben player at the tail end of one chief’s entourage, followed by another entourage the aben player of which uses a horn with human jawbones. This chief’s entourage concludes with a mmensoun group playing ivory horns. The next ensemble to come into view is a royal kete group with four drums and a bell. Kete drums are typically wrapped or painted in a black and red (funeral colors) checkerboard pattern. The next entourage includes an executioner’s drum (not played while in view). While the procession is momentarily stalled, another entourage with a kete ensemble passes on the street side. A moment later a fontomfrom ensemble comes into view. An executioner’s drum (this time played) and aben with human mandibles are part of the entourage to follow. Next there is a close-up of three men carrying their chief’s floor mat, throne, and footstool. The following group begins with the same trio of regalia and ends with an impressive fontomfrom set with two large from.

<cross dissolve>

The final few groups are then seen, ending with another kete group that includes dancers.

<fade out>

By this time, the first chiefs in the procession have arrived at the palace where they will soon be joined by the rest, the procession circumambulating the courtyard before settling into the reserved places beneath the canopies surrounding the courtyard. The final video segment captures a sense of the general cacophony at the palace.

Funeral for Paramount Chief

Between May 26 and 29, 1993, the citizens of the Anomabu Traditional Area marked the passing of their omanhene (paramount chief), Nana Amonu Aferi III. Although he passed away on February 1 at the age of sixty-six, his funeral rites were delayed for nearly four months while his family and the town of Anomabu planned the ceremonies, notified native residents of Anomabu now living elsewhere in Ghana and abroad in Europe and America, and raised the funds necessary to send their chief to the realm of the ancestors in proper style. I could of course capture only snapshots of the event’s entirety, but there should nonetheless be enough here to give you a sense of the incorporation of music making into an event of such importance to this one Fante community.